Philosopher Thomas Nagel's 1974 article "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?"1 argues that we might understand everything conceptually about a bat and perhaps even imagine a bat's point of view, but it remains impossible for humans to have the thoughts, motivations, or experiences of a bat.

I bring this up because, although our experiences shape a unique worldview within each of us, sharing a similar experience may not cause a similar perspective. We naturally presume that the machinery processing experiences in our minds is the same as the machinery in other minds. The following six books from three authors challenges that notion. How can I know what it is like to be you if your cognitive machinery—like that of a bat—differs from mine? Recognizing our neurodiversity is a first step to 1) gaining some conceptual understanding of each other and 2) understanding modularity and plasticity in the human brain.

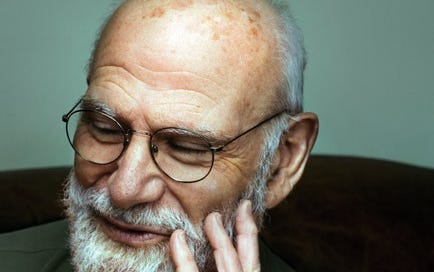

Do I Know You?: A Faceblind Reporter's Journey into the Science of Sight, Memory, and Imagination

I just finished a wonderful memoir2 of an award-winning science writer, Sadie Dingfelder. She has faceblindness (prosopagnosia, unable to recognize faces…even of close acquaintances), stereoblindness (amblyopia, viewing the world in 2D), Severely Deficient Autobiographical (aka episodic) Memory (SDAM, unability to recall recent experiences), and she cannot visualize (aphantasia, a lack of visual imagination, auditory imagination, inner monologues, and other senses of imagination). Despite all that, this book is both funny, insightful, and inspiring as we relive the author's unique childhood, marvel at her cognitive compensations, and share in her mid-life discovery that everyone does not think like her. Dingfelder's courage and persistence gains her an enviable career as a science journalist and a successful marriage despite a debilitating neurodiversity.

The second hero in this book is the human brain itself. A neurodiverse brain can solve problems—problems most of us take for granted—using compensating faculties. They are so successful that the author did not even recognize her own neurodiversity until her 40s.

Dingfelder's cognitive deficiencies come with a few benefits. These include:

painful memories or earworms (a melody that keeps repeating in one’s mind) do not trouble persons with aphantasia

Persons with aphantasia do not relive trauma or experience fear when not actually being confronted with it.

Stereoblind artists excel at drawing or painting3. Rembrandt van Rijn was stereoblind. Other artists suspected of stereoblindness include Alexander Calder, Marc Chagall, Chuck Close, Edward Hopper, Jasper Johns, Gustav Klimt, Willem de Kooning, Roy Lichtenstein, Thomas Moran, Robert Rauschenberg, Man Ray, Frank Stella, N. C. Wyeth and Andrew Wyeth.

Persons with faceblindness make friends easily because every person they meet is new. About six million Americans have faceblindness, including Jane Goodall, Brad Pitt, Johnny Depp, Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, and neurologist Oliver Sacks.

And that brings us to Oliver Sacks.

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and several other books

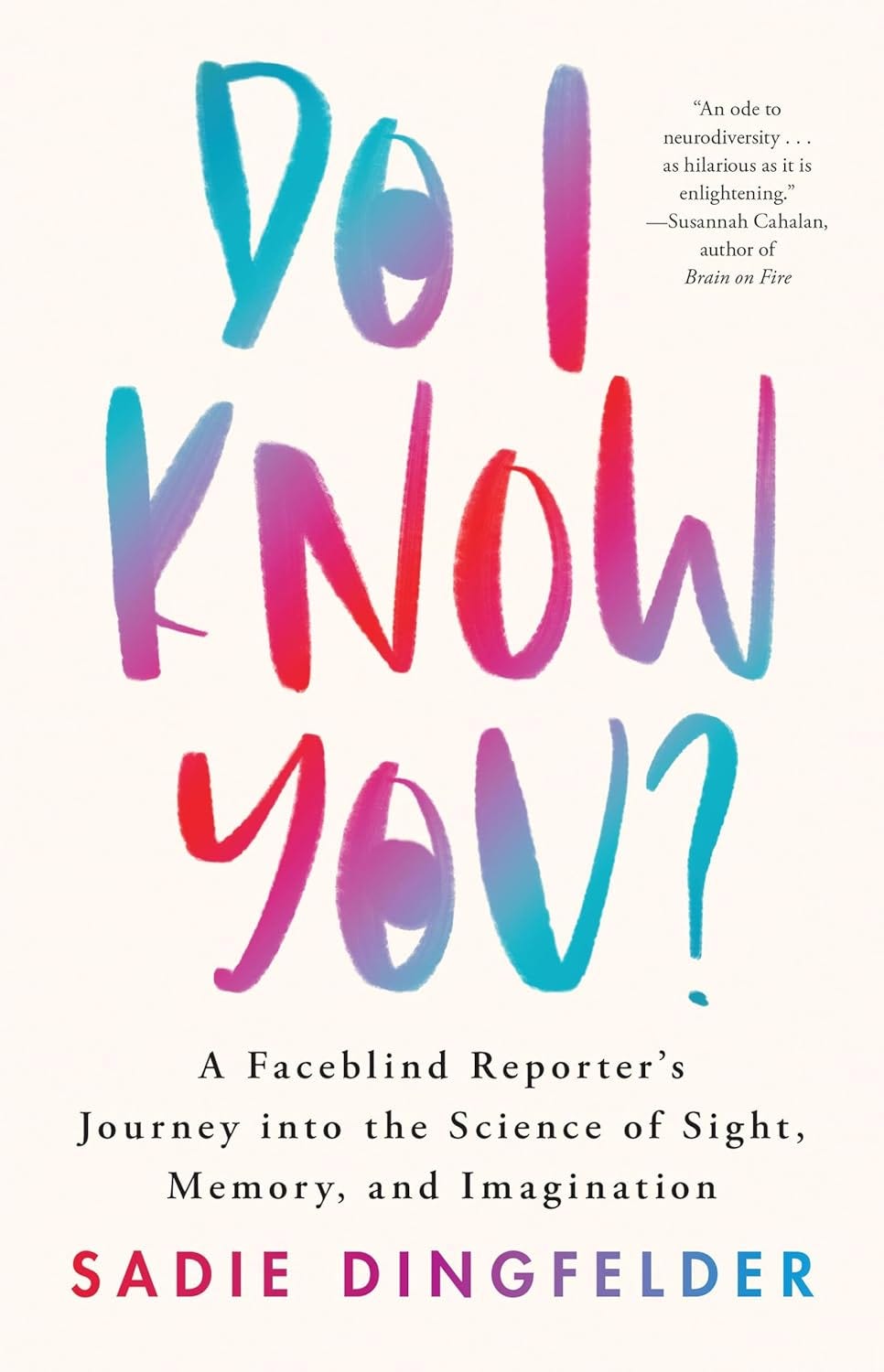

Oliver Sacks in 2013. Credit: Maria Popova via Wikimedia Commons

Oliver Sacks remains one of my favorite nonfiction authors. He was a British neurologist, naturalist, writer and he had faceblindness. He wrote, "My problem with recognizing faces extends not only to my nearest and dearest but also to myself. Thus, on several occasions, I have apologized for almost bumping into a large bearded man, only to realize that the large bearded man was myself in a mirror."4

In 1987, before neurodiversity was a word, I read Sacks' The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. This book is a collection of case histories of some of his patients. The title refers to one patient, Dr. P, who suffers from visual agnosia. Dr. P can identify individual features of objects but cannot recognize them or the whole objects they are part of. The title comes from an incident where Dr. P was leaving Sacks' office and grabbed his wife's head, mistaking it for his hat. The case histories are all bizarre and fascinating, but Sacks describes with compassion and sensitivity.

I have not read Awakenings but I enjoyed watching the 1990 Oscar-nominated biographic film based on the Sack's book starring Robert De Niro and Robin Williams as Sacks.

Other books by Oliver Sacks in my library include The Mind's Eye5 and An Anthropologist on Mars6. The title article of An Anthropologist on Mars is about Temple Grandin, a scientist and professor with autism. This article piqued my interest to learn more about Temple Grandin.

Animals in Translation and other books

Temple Grandin, Credits: Jonathunder, GFDL 1.2, via Wikimedia Commons

Rain Man was a 1988 road trip movie starring Dustin Hoffman and Tom Cruise. Kim Peek, an autistic savant, inspired Hoffman's character, Raymond. Raymond (and Peek) had some mental disability, but other mental abilities far above the average. This movie introduced many in 1988 to autism for the first time. In 1995, another autistic savant, Temple Grandin, published the biography Thinking in Pictures: My Life with Autism (with a foreword written by Oliver Sacks). This book provided the insight of both a person with autism and a scientist. When Dustin Hoffman studied for his role in Rain Man, he reached out to both Kim Peek and Temple Grandin.

Grandin describes her primary mode of cognition as visual thinking. If she cannot visualize a word, she struggles to understand it. Abstract concepts, metaphors, and figurative language become incomprehensible. Yet, she earned a PhD, has authored more than a dozen books and 60 scientific papers on animal behavior, and has designed humane equipment for meat processing plants. Her equipment designs handle 50% of all cattle in the U.S. and Canada. She credits her success in understanding animal behavior to her autism and symbolic cognitive deficit—being a visual thinker and being susceptible to sensory overload makes her more in tune with the animals she studies.

I have two of her books in my library: Animals in Translation and Animals Make Us Human.

Animals in Translation7 is the culmination of Grandin's 30 years of studying animal behavior combined with her insight as a person with autism. The best description of the book comes from her website, www.grandin.com where she lists her most controversial theories. You may not agree with every theory, but ignore them at your peril.

Animals in Translation…

redefines consciousness and argues that language is not a requirement for consciousness

categorizes autism as a way station on the road from animals to humans

explores the "Interpreter" in the normal human brain that filters out detail, creating an unintentional blindness that animals and autistics do not suffer from

applies the autism theory of ‘hyper-specificity’ to animals, meaning that there is no forest, only trees, trees, and more trees

argues that the single worst thing you can do to an animal is make it feel afraid

examines how humans and animals use their emotions, including to predict the future

compares animals to autistic savants, in fact declaring that animals may be autistic savants, with special forms of genius that normal people cannot see

explains that most animals have "superhuman" skills: animals have animal genius

reveals the abilities neurodiverse people, and animals, have that normal people don't

Animals Make Us Human8 is a book for anyone that lives with a pet or farm animal. It is a species-by-species guide to what and how they are thinking and how to provide them with the best possible life.

Both books draw on the work of Jaak Panksepp. Panksepp was an American neuroscientist and psychobiologist who coined the term "affective neuroscience". Affective neuroscience studies the neural mechanisms of emotion. It complements ‘cognitive neuroscience’. Panksepp’s book, The Archaeology of Mind: Neuroevolutionary Origins of Human Emotion9, provides an excellent introduction to affective neuroscience.

If you just want a taste of who Temple Grandin is and how she sees the world, I recommend watching the 2010 biographic movie, Temple Grandin, starring Claire Danes as Grandin. It is both entertaining and inspiring.

Each of these neurodiverse authors has made significant contributions to our society. In every case, their voice was unique and valuable. One might presume that they are exceptional. But it would be wrong to presume that neurodiversity is a binary thing (you have it or you don't) or that it represents a point on a spectrum. Both presumptions are false.

I am blessed to have been married to my spouse, Jean, for 42 years. I know Jean better than any other person on earth. Even though we are both engineers in education, career, and disposition (myself Electrical/Biomedical, her Civil), we each approach problems differently. As a result, I never approach things the way she would.

This has its benefits (and frustrations). As there are multiple dimensions to cognition (working memory, episodic memory, declarative memory, procedural memory, muscle memory, visual problem solving, symbolic problem solving, empathy, metacognition, habits, and affect), so there are multiple spectrums. Each of us has aptitudes at different locations on each spectrum. This diversity makes the Tom-Jean couple better at problem solving because collectively we have a larger set of potential solutions to choose from. Organizations that encourage diverse voices are the wiser for it.

I am drawn to books on neurodiversity because this variation along multiple dimensions provides insight into the brain's modular organization and each other. Like bats, we can never fully know each others experiences, motivations, or thoughts. It is a good reason to give people we find difficult a little slack.

Nagel, Thomas. “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” The Philosophical Review 83, no. 4 (October 1974): 435. https://doi.org/10.2307/2183914.

Dingfelder, Sadie. Do I Know You?: A Faceblind Reporter's Journey into the Science of Sight, Memory, and Imagination (p. 267). Little, Brown and Company.

Livingstone, M. S., & Conway, B. R. (2004). Was Rembrandt Stereoblind? The New England Journal of Medicine, 351(12), 1264–1265. http://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200409163511224.

Sacks, Oliver (30 August 2010). "Face-Blind Why are some of us terrible at recognizing faces?". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

Sacks, Oliver (2010). The mind's eye. Knopf/Random House.

Sacks, Oliver (1996). An Anthropologist on Mars (New ed.). London: Picador. xiii–xviii. ISBN 0-330-34347-5.

Grandin, T., & Johnson, C. (2005). Animals in translation: Using the mysteries of autism to decode animal behavior. Scribner/Simon & Schuster.

Grandin, Temple. Animals Make Us Human : Creating the Best Life for Animals. Boston :Mariner Books, 2010.

Panksepp, J., & Biven, L. (2012). The archaeology of mind: Neuroevolutionary origins of human emotion. W. W. Norton & Company.

Can you recommend any books that you have read on neurodiversity?

My question: How do all those artists paint in 3D when they only see in 2D? Excellent article, well worth a subscription.